Now narrated by Dagoth Ur!

Mars.

A name that instills both fear and fascination in the human mind, as the red

star travels across the night sky in ever stranger courses. The first record of

humans taking notice of our red neighbour comes from the Ancient Egyptians, who

gave it the name Har Deshur or Her Deshur (hieroglyphics rarely recorded

vocals), which means “Horus the Red”. This denoted the planet as being one of many

aspects of the sky god Horus, one of the most revered deities in their pantheon. For millennia this

would be the most benevolent association Mars had ever received, as the red

coloration made most of humanity think of more sinister things. The

Mesopotamians knew it under the name Nergal, the god of burning desert heat,

fire and plagues. In Hindu texts it was called Mangala, the god of anger. The

Greeks knew it either as Pyroeis, the fiery one, or Ares, the god of war and destruction. From

Ares the Romans would derive the god Mars, by whose name the planet is now widely

called. People in those times rarely thought of the planets as material

objects, but rather abstract things beyond human comprehension, likely put into

the roof-like firmament as signs from the gods. Thus the idea that someone - or

something - could be walking on their surface was rarely thought of. Do not

misunderstand me, such speculations did indeed exist at times in the writings

of ancient authors, such as Aristarchos, Plutarch or Lucian, but most of

humanity preferred cosmologies that stroked their own ego, such as Ptolemy’s

geocentric model, in which, with its aetherial planets, there was no place for

biology beyond the orbit of the Moon.

"Who shall dwell in these worlds, if they be inhabited? Are we or

they lords of the world?"

The

Copernican Revolution arrived in the Early Modern Period and came to the

momentous conclusion that Earth was not the centre of the universe, but was

in fact one of many planets circling the Sun. But if Earth is like the other

planets, does this also mean that those planets are like Earth? We find

early examples of such speculations in the writings of Giordano Bruno, who

wrote about life on the Moon and the Sun (then still thought to be a solid

object) and, already in the 16th century, noted that extraterrestrial life must

not necessarily resemble terrestrial variants, as even on Earth organisms have

found multiple solutions for the same functions (Heuser 2008). The same

century, German astronomer Johannes Kepler used Mars to solve one of the

greatest problems in cosmology. When viewed over a certain period of

time, the motion of the red planet across the night sky seems to go into the same

direction as the other planets, until the planet suddenly moves backwards in a

loop-like fashion to then resume its previous course (which may have led

ancient people to believe that the planet was steered by an intelligent force).

Kepler figured out why the planet went through such paradoxical motions: The

planets did not revolve around the Sun in perfect circles, as previously

assumed, but in ellipses, a realization which is today known as Kepler's First

Law of planetary motion. Kepler (1619) was also the first to mention the

possibility of inhabitants on Mars specifically, providing us with the above

quote. The astronomer would go on to write (and posthumously publish) possibly

one of the first science fiction novels, the Somnium, though it would be

about life on the Moon, instead of Mars, a notion that, as fanciful as it may

seem, might actually still have some merits, given recent findings about lunar

habitability in the deep past (Schulze-Makuch & Crawford 2018).

Fig. 1: One of the earliest detailed maps of

Mars by Giovanni Schiaparelli, showing (natural) channels of water. Note that the South Pole is here shown at the top, not the bottom.

As

telescopes improved, so grew the interest in Mars. In 1659, the very first

attempt at a map of the planet was drawn by Christiaan Huygens, showing what

would later be known as Syrtis Major Planum. 1666 Giovanni Cassini would be the

first to note the existence of a large ice cap on Mars’ southern pole, one of

the first signs that water of some form existed on the planet. In 1777, William

Herschel would discover that this polar cap would grow immensely during Martian

winter, proving that Mars had seasons. In around 1800, Honoré Flaugergues made

first mention of ochre-colored veils travelling across Mars’ surface, this

possibly being the first discovery of dust storms and therefore an atmosphere on

the planet. Catholic priest and astronomer Angelo Secchi made some of the first

detailed colour illustrations of Mars. In 1869 he reported two dark and linear

streaks across the surface, which he interpreted as channels, possibly bearing

liquid water. Two years before, Pierre Janssen and William Huggins had first

used spectroscopes to view Mars and came to the, albeit controversial,

conclusion that water vapor was present in its atmosphere. During the 1877

opposition, Asaph Hall discovered the two tiny moons of Mars. The same year,

Giovanni Schiaparelli produced the first detailed Mars maps, which showed

multiple features of the same type as seen by Secchi, which were again called

canali. Schiaparelli interpreted these as being natural, water-bearing

features, the Italian canali meaning channel (such as the one between Britain

and France). However, many foreign publications mistranslated these maps as

showing canals, a term which denotes an explicitly artificial structure.

1892, noted French astronomer Camille Flammarion reported seeing the same

features as Schiaparelli, but unlike him made an explicit connection to

extraterrestrial intelligence. Flammarion was the first to speculate that a

race of intelligent Martians, more advanced than humanity, used these grand

structures as an irrigation-system to redistribute polar meltwater into the

drier equatorial regions. Such ridiculously large construction projects were

thought possible and intuitive at the time for an advanced race, considering

that the Suez Canal was completed only a few decades prior and a few decades later the Panama Canal would begin construction.

Fig. 2. Mars’ vast system of canals, this time

imagined by Lowell to be of artificial origin by a dying Martian race.

Around

the same time, Pierre-Simon de Laplace’s nebular theory had become widely

accepted. The theory states that the planets farther from the sun formed out of

the primordial stellar nebula earlier than those closer to it. Thus, Mars was

an older planet than Earth, already past its prime and on the way to becoming

uninhabitable like the Moon (as a side-note, by the same logic, Venus was also

younger than Earth and thus imagined as quite prehistoric, sometimes even with dinosaurs). Based on this, American

astronomer Percival Lowell, one of the founders of planetology, speculated that

the canals were built by a Martian race that had not just become more advanced

than humanity by virtue of being older, but had also become quite

desperate, attempting to stave off extinction and planetwide desertification

with these monumental geoengineering projects. In 1894, he built the Lowell

observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, with the purpose of observing this dying

Martian civilization as good as was possible with the instruments of the time.

Lowell produced a great many maps of various and extensive canal-networks and

also speculated that the capital of the Martians was in Solis Lacus due to how

many canals he thought were crossing through that region.

“At most terrestrial men fancied there might be other men upon Mars,

perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to welcome a missionary enterprise.

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those

of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded

this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against

us.”

Greatly

inspired by such writings, a man of the name Herbert George Wells, who along with Jules

Verne would go on to become the founder of modern science fiction, wrote in

1897 a short story by the name of The Crystal Egg. In it, an antiquarian

discovers that a crystalline orb from his collection, if viewed in the right

angle of sunlight, acts as a window to view through another such crystal egg on

the surface of Mars. Inside a lush valley with a straight canal bisecting it,

the observer sees lichenous trees, red weeds, dim and primate-like bipeds,

insect-like animals and a rather bizarre Martian race. Wells’ intelligent Martians

are basically all head adorned by tentacles and come in two variants: Winged

Martians, which fly about Mars, live in houses that have only windows and no

doors and use the crystal eggs to observe the surface of the Earth and possibly

other planets. Then there are the wingless Martians, possibly of the same species but a

different caste, which amble about on the ground with their tentacles like

spiders and which seem to feed on the bipeds.

Fig. 3: One of the early covers for The Crystal

Egg, showing a winged version of the later octopus-like Martians, observing

Earth through a crystal orb, perhaps planning to invade.

The

same year, Wells began a story of serialized articles in Pearson’s Magazine, in

which the Martian civilization gave up their desperate attempts of maintaining Mars’ biosphere and instead used their greatly superior intellects and

technology to invade and colonize Earth with the help of enormous bionic

machines. In 1898 the articles were all compiled into a novel titled The War

of the Worlds. Probably being one the most famous science fiction stories

of all time, one might think that reiterating its details to the reader would

be superfluous. However, much like other classics, such as Moby Dick and

Frankenstein, this story is known by the general public more by its many

adaptations than by its original iteration. And those adaptations often tend to

do a great disservice to Wells’ Martians. Many details give away that The

War of the Worlds takes place in the same continuity as Wells’ previous

short story. The Martians which invade Earth greatly resemble the flightless

Martians of The Crystal Egg. Their cephalopod-like body consists of just

a huge skull with an equally large brain. The face consists of two large eyes

and a v-shaped mouth that resembles a fleshy beak. The beak is surrounded by up

to sixteen tentacles. No nostrils are present and the closest to an ear is a

tympanum at the back of the skull. There were no internal organs tasked with

digestion, instead the Martians fed by directly injecting their arteries with

the blood of lower creatures (humans). On their native Mars they “fed” for this

purpose on vaguely humanoid creatures, very likely those dim primate-like ones described in The

Crystal Egg, which were grey, bipedal and possessed a siliceous skeleton similar

to that of a glass sponge. Due to our shape resembling their cattle, the

invading Martians developed a great taste for human blood. The Martians also

spread the same kind of red weed as seen in the short story, in an attempt to

xenoform Earth into a second red planet.

Fig. 4: The inhabitants of Mars, as imagined by

H.G. Wells. An attempt at rendering genuinely alien life or instead a parody of what

humanity might become one day?

The

appearance of Wells’ Martians and their livestock may very well be seen as

commentary of the then anthropocentric view of aliens of the time. Even in the

novel, most people awaiting the opening of the Martian cylinder expected a

creature much like a human, with only minor differences, to crawl out, to then

be greatly shocked to see a bear-sized, cephalopodous creature. In view of the

many humanoid aliens that were designed even long after Wells’ time, this aspect

of the story still remains subversive. In fact, one could argue that the

appearance and behaviour of the Martians, as well as the general story of the

book, laid out the groundwork for the later cosmic horror genre. One H.P.

Lovecraft would have been an eight-year-old boy at the time of the novel’s

release and it is more than likely that he read Wells’ works.

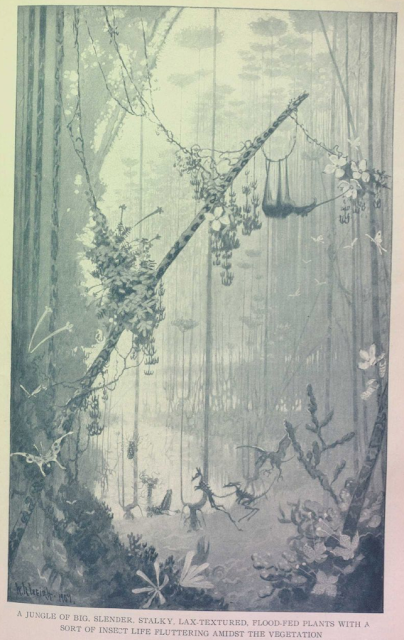

Fig. 5: Forest life on Mars as imagined by H.G.

Wells.

On

the other hand, the design of the Martians was also greatly influenced by

Wells’ own visions of what evolution might lead humanity towards. In Man of

the Year Million, Wells wrote that he imagines future humans to have

greatly reduced all of their organs, except for the brain and the hands, which

are both instrument and teacher of the brain. He also believed future humans to

externalise most of their digestive function. The Martians might therefore be

seen as the extreme endpoint of that development, with the body having become

all brain, the hands having become all tentacles and digestion having been

reduced to drinking the blood of animals. Indeed, the narrator of the novel

does speculate that the Martians may have once been humanoid in body form at

one point in their evolution. In this light, the Martians’ relation to their

humanoid livestock becomes interesting. Perhaps they were once closely related,

but had become starkly different through a similar relationship as seen between

the Eloi and Morlocks in Wells’ other novel, The Time Machine, just with

even more time for evolutionary divergence. All of this should also be viewed in

the light of Wells writing The War of

the Worlds as a form of critique of the colonialist geopolitics of his

time. As noted multiple times throughout the novel, the Martians in large part

do to the people of the British Isles what the British Empire had done a few

decades prior to the native people of Tasmania and many other colonized

countries. And is the way in which the Martians consume humans really all that

different from what we humans do to

animals and other forms of life we regard as “lower”? One could use all this to

argue that these Martians are only alien in their appearance, but not in their

nature.

Fig. 6: Mammal- and bird-like Martians as

imagined by H.G. Wells.

After

his short story and hit novel, Wells was not done with Mars quite yet. For a

March 1908 issue of the Cosmopolitan Magazine, Wells wrote an article

titled The Things which live on Mars.

Wells wrote his article in response to Percival Lowell’s then newest book Mars as the abode of life. While Wells enthusiastically

agreed with Lowell’s vision of Mars, he lamented that the astronomer in his

work never went into detail about the exact appearance of Mars’ biosphere,

especially regarding the question what sort of creature the intelligent Martian

civilization would have evolved out of. Thus, he engaged in something that

would today be called speculative evolution, with the creatures he imagined

being beautifully illustrated by William R. Leigh, who was otherwise known for

his Wild West art. Wells argued that plant life on Mars would be tall and thin,

with small leaves and needles and in general resemble plant life from Earth’s

deserts and mountain regions. Further he noted that something comparable to

insect life would exist, though he remained open to the question of if it would

be larger or smaller than on Earth. He also argued that there would be no

permanent aquatic life, such as fish, as the astronomy of his time indicated

that large bodies of water existed on Mars only in temporary form during the

summer, when the polar caps melted. Wells further reasoned that with

tall-growing plants there would be climbing animals and for an animal to be an

efficient climber it would need a spine, meaning there must be vertebrate life

on Mars. From here on out Wells’ vision of life on Mars becomes somewhat

chauvinistic in favour endothermic vertebrates, such as himself. He argues that

reptilian- or amphibian-type life may have long been outcompeted by now, as the

bird- or mammal-like Martians would be adapted a lot better to Mars’ current

cold climate (it should be noted that in real life, endothermic and ectothermic

animals on Earth do about equally well in both ends of the temperature-scale,

with warm-blooded small mammals and cold-blooded reptiles both thriving in

deserts and warm-blooded seabirds and cold-blooded fish and krill both thriving

in the polar regions).

Fig. 7: Wells’ highly advanced Martians,

similar to those from The Crystal Egg, but disappointingly more humanoid

(though this may be more due to the illustrator

William Leigh).

Thus,

Wells imagines the intelligent Martians to have descended from such mammal-like

Martian animals. Furthermore he thought they would almost assuredly have big

heads with big brains and forward-facing eyes atop an erect spine, as well as

big chests to breathe in the thin Martian atmosphere. He also thought it was

probable that they would be bipedal. To give him credit where it is due, Wells

is honest about not being able to answer any other details. He notes that they

could have more limbs than he speculates, that it is just as likely for the

Martians to have fur or feathers rather than naked skin and instead of arms

with hands they might use any other form of manipulatory organ, such as

tentacles or even trunks. Nonetheless, Leigh chose to illustrate Wells’

Martians as naked humanoids, though with bird-like feet, wings and tentacles

instead of fingers. In some ways this resembles the winged Martians

from The Crystal Egg and might indeed be an homage, though it is still disappointingly

anthropocentric compared to the cephalopods of The War of the Worlds. As

for the nature of Martian civilization, Wells wrote that most of the animal and

plant life he imagined previously in the text may already be extinct, as, per

Lowell’s writings, the Martians may have expanded their urban and agricultural

areas across the whole surface of the planet, in the process wiping out all

wildlife. This process he again deduced from what modern humanity is doing (and

continues to do) to its natural habitats.

Fig. 8: A green Martian from Barsoom. In many ways an ancestor to Warhammer/Warcraft-type orcs (and predating the Tolkien ones too while we’re at it)

At

the beginning of the 20th century, another man also became famous for his

writings on Mars, when in 1912 Edgar Rice Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan,

published the novel A Princess of Mars. The story follows the adventures

of the American civil war veteran John Carter, whose mind and body are mysteriously transported to the planet Mars, a world of ruins, fantastic

animals and various humanoid races. Burroughs’ Mars, named Barsoom by its

inhabitants, was greatly inspired by Percival Lowell’s writings (who in those texts fancifully imagined what it would be like for a human to stand on

Mars, for illustrative purposes to the reader). Like in Lowell’s vision, the

inhabitants of Barsoom transport water from the poles to the more equatorial

regions by use of massive canals, however, due to environmental degradation,

the global civilization of Mars has already collapsed and control over the

canals is quarrelled over by various warring city-states, while many other parts

of the planet have degraded into post-apocalyptic barbarism. The atmosphere has

also become so thin that the inhabitants have built atmosphere generators to artificially

keep it from dissipating, which may be Burroughs’ concession to more advanced

spectroscopy measurements of Mars’ atmosphere at the time. Life on Barsoom

differs in many respects from Wells’ vision, on account of Burroughs claiming

to have never actually read Wells’ work (Holtsmark 1986, though read on). Except for the native

race of the Green Martians, which have four arms, deep chests and tusked mouths, most

of the intelligent Martians are just humans with odd skin-colours, while most

of the Martian wildlife are close analogues to Earth-life with extra limbs. The exception may be the kaldanes, a race of crab-like brain-beings that bear more than a passing resemblance to Wells’ invaders, perhaps making Burroughs’ above claim a bit doubtful. The

Barsoom series, spanning eleven books that were released even after the main author’s death (1950) all the way into 1964,

would not become influential through any imaginative biology, but rather

through its storytelling and fun, escapist sci-fi concepts. It would go on to inspire

many people, among them the likes of Carl Sagan, to become astronomers and it founded the planetary romance genre. It would go on to inspire Perry Rhodan and

Flash Gordon, which in turn would become the basis for massive movie-industry

giants like Star Wars. The terms Jed(i) and Sith actually seem to have been directly lifted by George Lucas from the John Carter novels (Robert Zemeckis in fact once claimed that John Carter has become unfilmable today because Lucas had already gutted the books for all they were worth for his own movies). The character

Superman also originally began as an inversion of John Carter. Carter, being a human from higher gravity Earth, has superhuman strength on Mars relative to

its native inhabitants and can jump extraordinarily high. Superman, who in his

original iterations could not fly but just jump very high, has likewise superhuman

strength on Earth because he is an alien from a planet with even higher

gravity. Lastly, Burroughs’ Mars was the original desert planet of

science fiction, probably having one or two influences on Frank Herbert’s

Arrakis. In 1996, Barsoom would finally cross over with Wells’ Martians in the

tribute anthology War of the Worlds:

Global Dispatches, in which in one story, John Carter fights the original

Martians on the homefront. In 2012, literally a century after the original

book, John Carter finally received a movie adaptation. While it bombed at the

box office, I personally really enjoyed it and recommend watching it for the

escapism and the love it shows to the source material.

The Age of Uncertainty and the Great Disappointment

Despite

such fanciful speculations in fiction and popular science magazines, actual

science became increasingly more skeptical of Earth-like conditions and life on

Mars as the 20th century wore on. In the 1920s, better telescoping

and spectroscopic measurements showed that Mars’ atmosphere was even thinner

than assumed, had significantly less water vapor and oxygen than thought and

that temperatures ranged on the surface from -68 degrees Celsius to +7 degrees

at best. At least a lifeform such as John Carter would not have been able to

live here. There was also increasing doubt about the validity of Lowell’s

observations, with better telescopes indicating that the features he saw were

an optical illusion where the mind drew straight lines connecting dark patches

on the surface. But such explanations remained controversial, as no earth-based

telescope was powerful enough to see the red planet in crisp detail. And even

in the 30s, weird happenings on the red planet pointed towards possibly

intelligent activity, with large, green, flares being reported in 1937 (Davydov

1969). Was this a communication-attempt with Earth, a nuclear explosion or

simply volcanic activity? Until the age of spacecrafts, the question of life on

Mars in the mind of the scientist remained in a murky limbo. The general view

was that the conditions on the planet were too harsh to house spectacular

megafauna and a civilization of intelligent beings (and if such things ever did

exist on Mars, they would now be extinct), but the conditions were still

comparable enough to some extreme regions on Earth that they would permit the

existence of primitive plants and animals on the surface. A great example of such

a low-complexity Martian biosphere comes from the 1957 documentary Mars and Beyond, directed

by animation legend Ward Kimball as part of the Disneyland TV series. Apart

from hilariously pointing fun at sci-fi tropes of the time, the program also

presents a fantastic 5-minute segment that shows in a starkly realistic

style the possibilities of extremophile critters on the Martian surface. A big

argument at the time for the existence of surface life on Mars was that

telescopes showed green-blue patches across the surface of the planet change

shape, extent and colour with the changing of the seasons. This was often taken

as an unmistakeable sign of patches of vegetation responding to the winter and

summer seasons, with scientific papers on the Martian biosphere basing

themselves off such observations all the way into the early 60s (Salisbury

1962).

Fig. 9: Changing colour patterns on Mars, once taken

to be signs of vegetation, but now known to be caused by dust storms.

With

the age of robotic spacecraft came a great punch to the gut for any such speculations.

Mariner-4 successfully launched in 1964 and provided the first close-up

photographs of Mars’ surface in 1965. What they showed was a lifeless, moon-like

desert, with an atmosphere even thinner than previously expected and no

magnetosphere to shield the surface from harmful radiation. Despite this, prominent

figures such as Carl Sagan still defended the idea of surface life on Mars. Sagan

argued that Mariner-4 had photographed only a tiny part of the Martian surface

and at such a low resolution that, had the probe orbited Earth, it would not

even have been able to detect human civilization (Kilston et al. 1966). A year

later, he wrote an

article for National Geographic, accompanied by an illustration of Martian

surface life he deemed realistic. At night the plantlife folds up to protect

itself and the animals shield themselves with siliceous shells from harmful

UV-radiation.

Fig. 10: 1975 renderings of Martian surface

life, made by an unnamed artist at the JPL.

Despite

Sagan’s arguments, further probing by robotic spacecrafts increasingly showed

that Mars was more inhospitable than anyone would have thought, the last hopes

for surface life likely dying out in 1976 with the (albeit still somewhat

controversial) findings of the two Viking Landers. Only a year prior an unknown

artist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory had produced his artwork of sessile,

silicon-based life on the surface of Mars. While conditions may have once been

more hospitable in the deep past, today we know that Mars’ modern, mainly

carbon dioxide atmosphere has only 0.6% of Earth’s air pressure, which,

combined with the extremely low temperatures, means that apart from toxically

salty brines, water can only exist in a solid or gaseous state. Its surface is

constantly baked in harmful radiation, which furthermore produces perchlorate

salts that are toxic to most life. The supposed patches of vegetation turned

out to have been seasonal dust storms instead, Lowell’s canals were nowhere to

be found and the Face on Mars of the Cydonia region was but an ordinary hill

viewed at a funny angle. While the search for life on our neighbouring planet

still valiantly continues, nobody expects anymore to find it on its surface. If

life exists on Mars, then today only in shielded and warmer sub-surface

habitats deep underground and, in all likelihood, only in microbial form.

Recent findings by rover Curiosity of seasonal methane and oxygen releases may

support such subterranean biospheres, as well as possible microscopic

ichnofossils inside Martian sediments and meteorites (Baucon et al. 2020).

But what if?

With

apologies to any microbiologist reading this, but where is the fun in some bacteria?

What if we turn back the clock to 1964 and have Mariner-4 first lay its eyes on

a different, slightly more habitable Mars, with just a little more air and a

little more heat, and have the probe detect some oases of life inside the deserts and

craters? Nothing too fancy, no civilizations, no giant beasts, just

extremophile fauna and flora trying to make its best out of living on a harsh,

but still liveable Martian surface. In the words of the Artilleryman: We’ll

start all over again!

On

this website you will explore this different Mars through the accounts of the manned

space mission Horus 2, which will take you across the dunes, dust plains, glacial lakes and

cratered canyons of Mars and showcase all its unique wildlife. This will be a

Mars as envisioned by the scientists and artists of the 50s and 60s, though it

will attempt to take into account some modern data about the red planet as well.

Fig. 11: A primitive antitrematan, during a time

when Mars still had an ocean. You will not get to meet this critter on

your journey through this site, but will instead meet some of its descendants.

Before

I release you onto Mars, I need to mention that all of what you will be reading

here will merely be a teaser for what is to come. I have been working for a

couple of years now on a physical book about Martian life, however in billion-year-old

fossil form. While Har Deshur will be a throwback to an alternate modern Mars, Life on a Dead Planet, as the work is

currently titled, will play on a Mars that is the same today as in our own timeline

and will instead be a fictional future paleontology textbook that will deal

with the fossils that have survived from the planet’s deep past when it still

had oceans. Nonetheless, you will see many familiar clades and lifeforms across

both works. When Life on a Dead Planet will come out I cannot say, as it

is undergoing a major rework, however you can read some of the earliest drafts

of some of the chapters on my Patreon if

you are interested enough.

Now do like Arnold Schwarzenegger and get your ass to Mars!

References:

- Baucon,

Andrea et al.: Ichnofossils,

Cracks or Crystals? A Test for Biogenicity of Stick-Like Structures from Vera

Rubin Ridge, Mars, in: Geosciences, 10, 2020.

- Davydoc,

V.D.: New Interpretations of Mayeda’s flare on Mars, in: Soviet Astronomy, 13,

1969.

- Heuser, Marie-Luise: Transterrestrik in der

Renaissance: Nikolaus von Kues, Giordano Bruno, Johannes Kepler, in: Michael

Schetsche/Martin Engelbrecht (Hrsg.): Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen.

Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft, Bielefeld

2008.

- Holtsmark,

Erling: Edgar Rice Burroughs, Boston 1986.

- Kepler,

Johannes: Harmonice Mundi, Linz 1619.

- Kilston,

Steven; Drummond, Robert; Sagan, Carl: A

search for life on Earth at kilometer resolution, in: Icarus, 5, 1966, p.

79 – 98.

- Lowell,

Percival: Mars as the abode of life, Flagstaff 1908.

- Salisbury,

Frank: Martian

Biology. Accumulating evidence favors the theory of life on Mars, but we can

expect surprises, in: Science, 136, 1962, p. 17 – 26.

- Schulze-Makuch,

Dirk; Crawford, Ian: Was There an Early Habitability Window for Earth's

Moon?, in:

Astrobiology, 18, 2018, p. 985 – 988.

- Wells,

Herbert George: The things which live on Mars, in: Cosmopolitan Magazine, 44,

March 1908, p. 334 – 342.

Image Sources: